Chinese Dragon Names (Pinyin): Dragon Kings & Nine Sons

Chinese Dragon Names (with Pinyin): Mythic “Long” You Can Actually Trace

A lot of “Chinese dragon name” lists are just vibes. If you want names with real roots—classics, folk tradition, and famous stories—start here. Each entry has the Chinese, the pinyin, what it’s known for, and why the name feels the way it does.

What a Chinese Dragon Represents (So You Pick Names That Fit)

In Chinese culture, dragons are usually beneficial, not “boss monsters.” They’re tied to water, rain, movement, and life, and they also became a symbol of cosmic yang and imperial authority in later history.

If you’re naming a character, a “dragon name” often signals status, force of nature energy, or someone who changes the situation around them—socially, politically, or literally with weather.

Classic Myth Dragons You’ll See Again and Again

Yinglong (应龙, Yìnglóng) — the Winged Dragon Who Wins Wars

Source: Shan Hai Jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas). Yinglong is the famous “winged dragon” linked to big mythic campaigns—helping defeat Chiyou, and later assisting flood control by carving waterways with its tail.

- Name vibe: a high-tier, “mythic general” dragon.

- Best for: warlords, guardians, ancient weapons, elite clans.

- Easy English rendering: Yinglong / Ying Long.

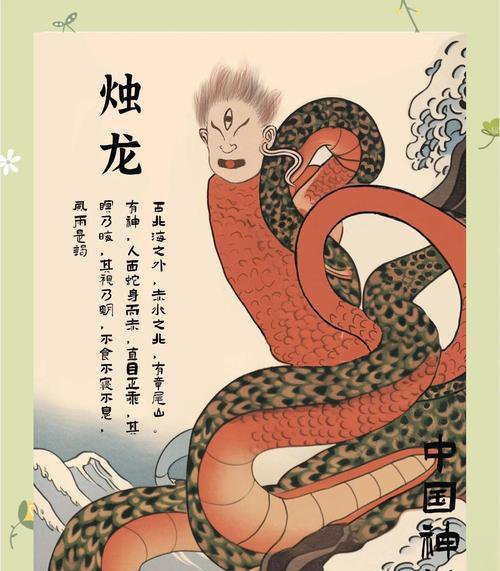

Zhulong / Zhuyin (烛龙 / 烛阴, Zhúlóng / Zhúyīn) — the Day-Night Maker

Source: Shan Hai Jing. Zhulong (also called Zhuyin) is described as a god-like being with a human face and snake body; its eyes and breath set the rhythm of day/night and seasons. It’s basically “cosmic schedule management,” dragon edition.

- Name vibe: creation-myth scale, reality-bending, ancient-law energy.

- Best for: primordial dragons, time/season motifs, “the one everyone fears.”

- Pronunciation note: Zhu- (like “joo”), -long (like “long”).

Qinglong (青龙, Qīnglóng) — the Azure Dragon of the East

Source: astronomy + Five Phases tradition. Qinglong is one of the Four Symbols (Four Celestial Beasts), tied to the East, spring, and wood, and also names the eastern group of seven lunar mansions.

- Name vibe: noble, orderly, “guardian of a direction,” elite-but-not-evil.

- Best for: empires, royal guards, sacred armies, eastern temples.

- Quick pairing ideas: Qinglong + “spring,” “jade,” “east wind.”

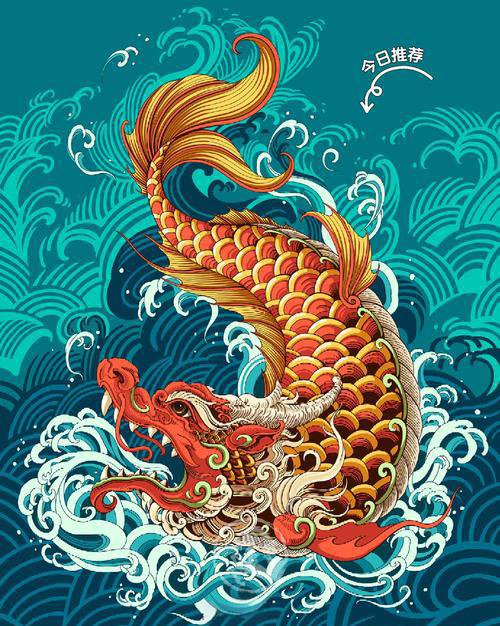

Jiaolong (蛟龙, Jiāolóng) — the Flood Dragon Under Deep Water

Source: classical usage + later interpretation. Jiaolong often means a dragon-like water creature linked to deep pools and flooding—less “celestial mascot,” more “river that can ruin your week.”

- Name vibe: dangerous waterpower, cultivation trials, lurking menace.

- Best for: underwater bosses, river gods, “half-dragon” bloodlines.

- English rendering: Jiaolong / Jiao Long (both are common).

Kui (夔, Kuí) — the One-Legged Storm-Bringer

Source: Shan Hai Jing traditions. Kui is described like a powerful beast associated with thunder and storms, famously said to cause wind and rain when entering or leaving water; its hide is used to make a drum whose sound carries for miles.

- Name vibe: thunder, battle drums, unstoppable momentum.

- Best for: war banners, “storm oath” clans, mythic percussion (seriously).

- Spelling tip: it’s Kuí, not “Kui Long” (unless you’re naming a hybrid).

Shuihui → Jiao → Long → Jiaolong (水虺→蛟→龙→角龙) — the “Dragon Growth Ladder”

Source: later lore (often cited from Shu Yi Ji). One famous line describes a progression: a water hui (shuihui) becomes a jiao, then a dragon, then a horned dragon (jiaolong/角龙) over long ages.

- Why it’s useful: it gives you a clean naming system for “forms” or “stages.”

- Easy naming trick: early-stage names feel smaller and sharper; late-stage names feel grand and ceremonial.

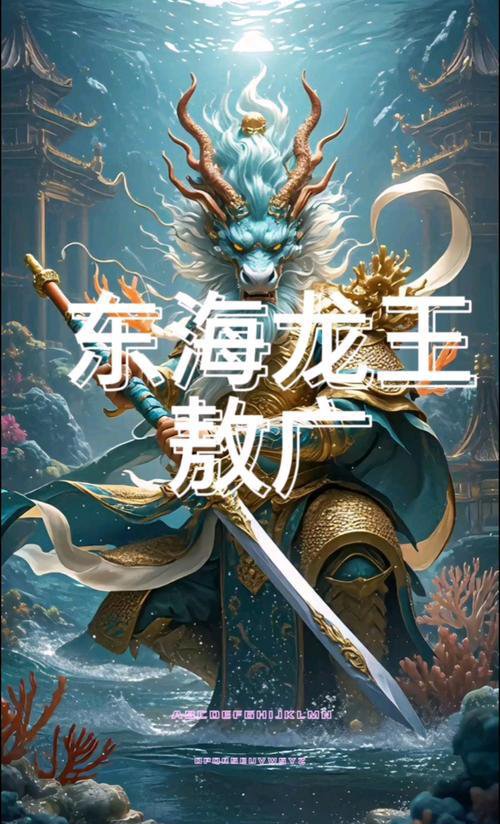

The Dragon Kings in Journey to the West (Water Bureaucracy, but Make It Myth)

By the time of Ming-era novels like Journey to the West, dragons often look like a full-on official system—titles, jurisdictions, and “sorry, we need approval from Heaven.” The Four Sea Dragon Kings are a famous set: Ao Guang, Ao Qin, Ao Run, Ao Shun.

Ao Guang (敖广, Áo Guǎng) — Dragon King of the East Sea

Ao Guang is typically treated as the most prominent of the four sea kings. He’s the one people remember from the “Dragon Palace” scenes and the whole vibe of ocean wealth and strict hierarchy.

Ao Qin (敖钦, Áo Qīn) — Dragon King of the South Sea

Ao Qin rules the South Sea in the classic quartet. In naming, Qin (钦) feels official—respect, authority, “this person has rank.” :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

Ao Run (敖闰, Áo Rùn) — Dragon King of the West Sea

Ao Run is the West Sea Dragon King in the well-known set. The character Run (闰) also has a “calendar” flavor in Chinese, so it can read subtly refined instead of purely brutal.

Ao Shun (敖顺, Áo Shùn) — Dragon King of the North Sea

Ao Shun is the North Sea Dragon King in the standard lineup. The character Shun (顺) suggests “to follow / to be in accord,” which makes this name feel disciplined, even when the character is terrifying.

Jinghe Dragon King (泾河龙王, Jīnghé Lóngwáng) — the Rain Bet That Ends Badly

This story is a classic: the Jinghe Dragon King changes the rain schedule against heavenly orders after a wager, and ends up executed—famously tied to the “beheaded in a dream” episode and the chain of events around Emperor Taizong.

Ao Lie, the White Dragon Horse (敖烈, Áo Liè) — the Dragon Who Becomes a Mount

Ao Lie (often called “Little White Dragon”) is the West Sea Dragon King’s son who becomes the monk’s white horse. It’s a great example of dragon identity being folded into duty, redemption, and long-haul loyalty.

“Nine Sons of the Dragon” (龙生九子): Not True Dragons, but Iconic

This idea gets popular in later tradition and is strongly associated with Ming-era discussion; the exact list varies across sources, so you’ll see alternate “ninth sons” in different tellings. One famous textual anchor is Yang Shen’s Sheng’an Ji (升庵集) talking about “dragon has nine sons, each with its own preference.”

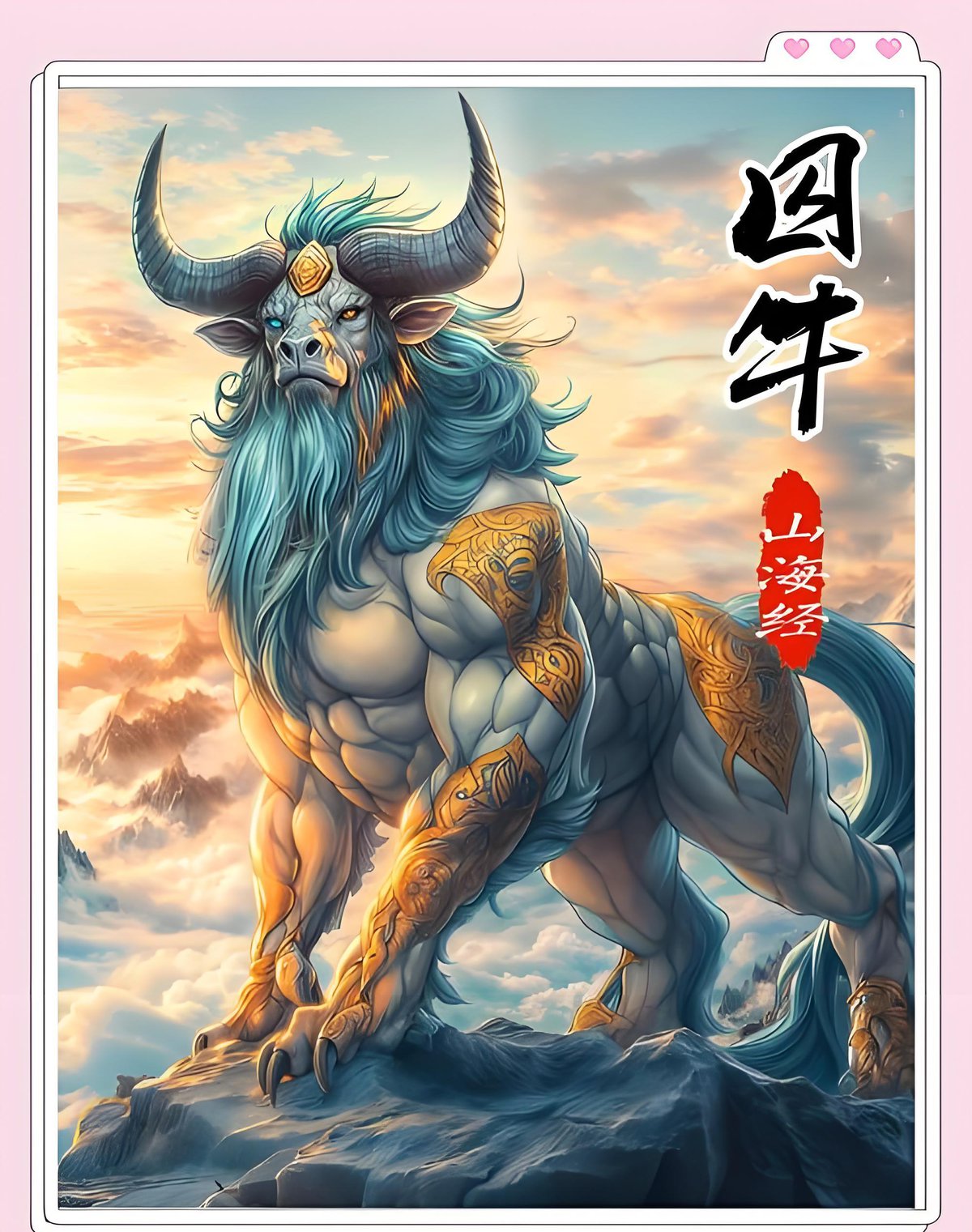

Qiuniu (囚牛, Qiúniú) — the Music Lover

Qiuniu is linked to musical taste and often shows up as instrument decoration. If you want a “cultured dragon-bloodline” name, this one does the job fast.

Yazi (睚眦, Yázì) — the Fighter

Yazi is the go-to “battle appetite” son, commonly carved on weapons. The name itself looks sharp, and it reads like danger even before you explain it.

Chaofeng (嘲风, Cháofēng) — the Roofline Daredevil

Chaofeng is associated with heights and watching the distance, often placed on roof corners. This is a great name for scouts, sentinels, or anyone who “sees trouble coming.”

Pulao (蒲牢, Púláo) — the Loud One

Pulao is tied to roaring and is often used on large bells. If your character is “small body, huge voice,” this name is basically a cheat code.

Suanni (狻猊, Suānní) — the Incense-Sitter

Suanni is lion-like and connected with sitting calmly and enjoying incense smoke, so it appears on incense burners and seats. It’s a perfect name for a proud guardian who barely moves… until they do.

Baxia / Bixi (霸下 / 赑屃, Bàxià / Bìxì) — the Heavy Lifter

This one loves carrying weight and is famous as the stone-stele base creature. If you want “strength + endurance + reliability,” this is the cleanest pick.

Bi'an (狴犴, Bì'àn) — the Justice Face

Bi'an is tiger-like and linked to courts and prisons, symbolizing judgment and law. It’s a solid name for a stern magistrate character or a “dragon who enforces rules.”

Fuxi (负屃, Fùxì) — the Bookish One

Fuxi is associated with love of writing and inscriptions, often carved around steles. Use it when you want “scholar energy,” but still inside a dragon myth frame.

Chiwen (螭吻, Chīwěn) — the Fire-Guard on the Roof

Chiwen is commonly placed on roof ridges and is linked to swallowing water or guarding against fire in architectural symbolism. It’s a strong name for a protector who “eats disasters.”

Huanglong (黄龙, Huánglóng) — the “Central” Dragon

Huanglong is tied to the center in Five-Phase / directional symbolism, often linked with earth (土) and imperial auspiciousness. It’s sometimes treated as the one that “outranks” the four directional beasts by sitting at the center of the system.

- Name vibe: legitimacy, mandate, “the throne recognizes me.”

- Best for: emperors, founders, central capitals, “final boss but lawful.”

Modern Chinese Names That Use “龙” (Because Dragons Never Left)

“龙” (lóng) shows up in real names because it’s a compact symbol: power, luck, and “aim high.” And in pop culture, it also became a brand for martial arts charisma.

Jackie Chan — Cheng Long (成龙, Chéng Lóng)

His stage name literally contains “dragon,” and you can feel the intent: momentum, strength, cinematic impact. Even if you don’t speak Chinese, “Cheng Long” just sounds like someone who hits hard and keeps moving.

Bruce Lee — Li Xiaolong (李小龙, Lǐ Xiǎolóng)

“Xiaolong” means “little dragon,” which is funny because the legacy is anything but little. It’s one of the most famous “龙” names globally, and it cemented the dragon = martial legend association for a lot of audiences.

John Lone — Zun Long (尊龙, Zūn Lóng)

“Zun” (尊) leans into “honored / revered,” so the full name reads like “revered dragon.” It’s a clean example of how one character can shift the whole tone of “龙” from fighter to prestige.

Bruce Leung — Leung Siu-lung (梁小龙, Liáng Xiǎolóng)

Another “little dragon,” and he was even grouped with other famous “dragon-named” martial arts stars in Hong Kong pop culture. If you’re studying naming trends, this is the pattern in the wild.

FAQ: Chinese Dragon Names (Fast Answers)

How do you pronounce “龙” in English letters?

It’s lóng (second tone), usually written Long in pinyin. In older English writing you may see “lung,” but pinyin “Long” is the standard today.

Is every Chinese dragon a “nice dragon”?

No—Chinese dragons aren’t automatically cute or friendly. A name like Jiaolong leans toward floods and danger, while Qinglong reads as orderly and auspicious.

Are the Dragon Kings “real mythology” or just novels?

Dragon Kings exist in religion and folk belief, and novels like Journey to the West made them feel like a full bureaucracy with personalities. If you want names that feel “official,” the Ao- (敖) kings are perfect.

Is “Nine Sons of the Dragon” fixed canon?

It’s famous, but the lineup varies across tellings—different sources swap in different “sons.” If you’re naming for a story, pick the version that matches your theme and stick with it consistently.

Can I use these names for a character or brand?

Yes, and the trick is matching the semantic mood. “Yinglong” screams mythic hero-force; “Zhulong” screams cosmic dread; “Huanglong” screams central legitimacy.

How do I make a new Chinese-style dragon name that doesn’t sound fake?

Pick one strong trait word (wind, river, iron, dawn, thunder) and pair it with 龙 (Long), or use an established name as a “title” and add a personal name. If you keep it short and meaning-forward, it’ll read believable fast.