15+ Nicknames for the Yellow River, China's Most Sacred Stream

The Yellow River isn’t just a river in China. For a long stretch of history, it was the river—so central that people simply called it 河 (Hé), “the River.” Over time, as the river changed (and so did politics, religion, and language), it picked up a whole collection of nicknames—some official, some poetic, some painfully practical.

Official, text-backed names (the ones you actually see in classics and historical records)

| Period | Name (Chinese + pinyin) | Literal meaning | Where it shows up | What it’s saying about the river |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Qin → Han | 河 (Hé) | “the River” | Classics and early histories; also used as a default label in many texts | When people said “the river,” they meant this one—status doesn’t get more official than that. |

| Pre-Qin → Han | 河水 (Hé Shuǐ) | “river water” | Appears in early writing traditions; later quoted in works like Water Classic Commentary | A slightly more descriptive way of saying “the River,” often used when the text is being formal or explanatory. |

| Warring States → Han | 大河 (Dà Hé) | “Great River” | Historical writing traditions (often when emphasizing scale) | Less “nickname,” more “bow of respect.” You call it big because it is. |

| Classical geography | 九河 (Jiǔ Hé) | “Nine Rivers” | Early geographic/hydrology descriptions of the lower reaches | A nod to how the lower Yellow River could split into multiple channels—messy, shifting, and hard to pin down. |

| Western Han | 中国河 (Zhōngguó Hé) | “China River” / “Central States’ River” | Book of Han《汉书》(Hàn Shū), Records of the Western Regions《西域传》(Xīyù Zhuàn) | It frames the river as the “home river” of the central world—very on-brand for an empire calling itself “the center.” |

| Qin | 德水 (Dé Shuǐ) | “River of Virtue” | Records of the Grand Historian《史记》(Shǐjì), Basic Annals of Qin Shihuang《秦始皇本纪》(Qín Shǐhuáng Běnjì) | A political rename: Qin Shihuang tied the dynasty to “water virtue” (水德 shuǐ dé) and even renamed the river to match. |

| Han → later | 浊河 (Zhuó Hé) | “Muddy River” | Classical usage; later dictionaries explicitly say it refers to the Yellow River | Not poetic—just accurate. The river carries heavy silt, and people noticed. |

| Han → today | 黄河 (Huáng Hé) | “Yellow River” | Book of Han《汉书》(Hàn Shū) and later literature | The name that stuck. “Yellow” points to the loess (fine yellow silt) the river carries. |

| Modern era | 母亲河 (Mǔqīn Hé) | “Mother River” | Modern cultural usage (media, education, museums) | Less a literal name, more a national compliment: the river as a giver of life and civilization. |

1) 河 (Hé): when “the River” meant one specific river

If you’re reading old texts and see 河 (Hé) with no “yellow” attached, don’t assume it’s generic. In many early contexts, “the River” was shorthand for the Yellow River—kind of like saying “the City” and meaning New York (depending on who’s talking).

2) 中国河 (Zhōngguó Hé): a name with serious “center of the world” energy

The phrase 中国河 (Zhōngguó Hé) shows up in the Book of Han《汉书》(Hàn Shū), where a river is described as emerging at 积石 (Jīshí) and being “the China River.” It’s a worldview in one label: the river belongs to the “Central States” (中国 Zhōngguó).

3) 德水 (Dé Shuǐ): the Qin dynasty tried a rebrand

Qin Shihuang didn’t just standardize weights and measures—he also played naming games. Following the Five Phases idea (五行 wǔxíng), he claimed Qin had “water virtue,” and the historical record says he renamed 河 (Hé) as 德水 (Dé Shuǐ).

4) 浊河 (Zhuó Hé) → 黄河 (Huáng Hé): the color shift becomes the identity

Once the river’s silt load became impossible to ignore, names calling it “muddy” made perfect sense. Eventually 黄河 (Huáng Hé) became the standard, and from then on the “yellow” wasn’t just description—it was the brand.

Folk nicknames (what people say when they’re living with the river, not writing about it)

“铜头铁尾豆腐腰” (Tóng tóu tiě wěi dòu fu yāo): copper head, iron tail, tofu waist

This one is famous because it feels like field notes from people who’ve had enough. It describes different stretches of the river’s temperament, and the “tofu waist” part—豆腐腰 (dòu fu yāo)—is used for sections considered especially prone to trouble, because tofu breaks.

Modern reporting from the Yellow River Conservancy Commission (黄河水利委员会 Huáng Hé Shuǐlì Wěiyuánhuì) points out places like 兰考 (Lánkǎo) as a classic “豆腐腰” stretch, with a long history of breaches and flooding pressure.

黄大王 (Huáng Dàwáng): the “Yellow River King” people built temples for

黄大王 (Huáng Dàwáng) is the kind of nickname that only makes sense in a flood-prone world: when water decides your fate, you start treating water-control heroes like saints. In some areas, “Huáng Dàwáng” became a local protective figure tied to Yellow River stories and temples.

黄河仙子 (Huáng Hé xiānzǐ) / 曹娘娘 (Cáo niángniang): a river goddess with regional roots

Along parts of the Yellow River in Shanxi (山西 Shānxī) and Shaanxi (陕西 Shǎnxī), you’ll hear folk stories about a female spirit connected to the river—often called 黄河仙子 (Huáng Hé xiānzǐ) or 曹娘娘 (Cáo niángniang). Think of it as a community’s way of giving the river a face—and maybe someone to negotiate with.

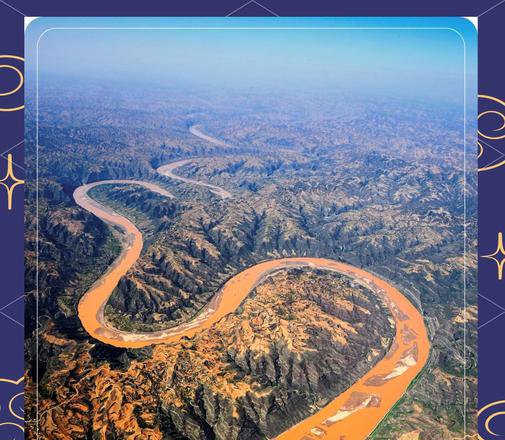

巨龙 (Jùlóng): the “giant dragon” metaphor

Look at the Yellow River on a map and you’ll hear people say it curls like a dragon—巨龙 (Jùlóng). It’s not a formal name in the classics, but it’s a common modern metaphor because, honestly, it does look like it’s twisting through the land like it’s alive.

What foreigners call it (and what those names reveal)

- The Yellow River: the straightforward translation of 黄河 (Huáng Hé).

- “China’s Sorrow”: the nickname you’ll see in English-language references, tied to the river’s long history of destructive flooding.

- “Cradle of Chinese Civilization”: the flattering one—because early Chinese states and cultures grew up around this basin.

- “Mother River (of China)”: an English echo of 母亲河 (Mǔqīn Hé), used in cultural or documentary-style contexts.

Quick backstory: where the river starts, why it misbehaves, and why the nicknames make sense

Origin and route (the 20-second version)

The Yellow River rises in the Bayan Har Mountains—巴颜喀拉山 (Bāyánkālā Shān)—in Qinghai (青海 Qīnghǎi), on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. From there it runs all the way to the Bohai Sea (渤海 Bóhǎi), and it’s China’s second-longest river.

Why it floods so often

The short answer is silt. The river carries enormous amounts of fine sediment (often linked to the Loess Plateau), and when that sediment gets deposited downstream, it can raise the riverbed. In the lower reaches, that’s a recipe for overflows that spread across a flat plain—exactly the kind of situation that earns a nickname like “China’s Sorrow.”